60-Year Legacy of Industrial Pollution Holds Warning for Oil and Gas Communities

The Grassy Narrows First Nation in northwestern Ontario has struggled with industrial mercury pollution since the 1970s. Is this what Alberta oil and gas communities can look forward to?

A sordid, 62-year-old history of polluted water and shattered lives is a stain on Canada’s claims to reconciliation with First Peoples. And it’s a prequel of what may be in store for Western Canadian communities, Indigenous and not, as a declining oil and gas industry offloads its orphaned and abandoned wells.

This past week, 100 members of the Grassy Narrows First Nation along with thousands of supporters marched to the Ontario legislature. They were bringing the devastating story of mercury poisoning and its impact on two northwestern Ontario Ojibwa communities back into the headlines and to the top of everyone’s email.

Their message: “We’re not going away.”

For those of us who spend most of our time thinking about energy and climate change, the parallels back to the story of mercury poisoning in northwestern Ontario should be chilling. But it’ll take a bit of history for those connections to make sense.

Just Stop Drinking Water

The pulp and paper plant that came to be known as the Reed Mill first opened in 1909 in Dryden, east of Kenora, Ontario, and mercury poisoning from the mill caused one of Canada’s worst cases of environmental poisoning in the 1960s and 70s. Wanton dumping of a dangerous neurological toxin between 1962 and the early 1970s poisoned the English-Wabigoon river system and contaminated the fish that were a staple food for members of the Grassy Narrows First Nation and the then Whitedog band, now part of the Wabaseemoong Independent Nations.

“By 1970, the river was polluted with chemical waste. This spread to the Winnipeg River and eventually to Lake Winnipeg,” states the Wikipedia entry on Dryden’s pulp and paper industry. “As a result, the people of Grassy Narrows and Whitedog suffered from mercury poisoning, including Minamata disease. Mercury never dissolves and is bioaccumulative [pdf].”

“About 850 First Nations people were living on the two reserves when the mercury issue arose, and they were told to stop eating fish and drinking water,” the Wikipedia authors write. “The commercial fishery and fishing guides services were forced to close, resulting in mass unemployment in the community.”

That didn’t stop Dryden Chemicals, a subsidiary of UK-based Reed International, from proposing a second mill in 1977, before a recommendation from the provincial Royal Commission on the Northern Environment stopped the plan in its tracks. In 1985, company officials were still deflecting blame for the disaster to naturally-occurring mercury in the English-Wabigoon system, despite sampling that showed much higher mercury levels in fish taken from the area.

Fast forward decades, and the word “mercury” doesn’t even show up in a 100-year history [pdf] of the Dryden Mill published in 2014 by The Forestry Chronicle, which styles itself as a “professional and scientific forestry journal” produced by the Canadian Institute of Forestry.

In 2019, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the plant’s most recent owners—Weyerhauser Co. and the former Resolute Forest Products—were responsible for cleaning up after themselves. Fast forward another five years and the mill is still in production, and Wikipedia says the federal government is building a $20-million treatment clinic for local people whose health has been destroyed by mercury poisoning.

Grassy Narrows Then and Now

One of the first things I ever remember seeing on (still black and white) TV was an investigative feature in the early 1970s on what was then known as Minamata disease, the devastating neurological impacts of mercury poisoning on people and other living things. The two images burned into my memory were the jerky, uncoordinated spasms of a cat in Japan that had eaten mercury-laden fish and the halting, uncontrolled movements of people who’d done the same.

In my first full-time journalism job seven or eight years later, Ontario North of 50° was part of my geographic beat, working from Ottawa by long distance phone. Mercury poisoning at Grassy Narrows and Whitedog was an old, festering issue even then, just one of the half-dozen or so burning, urgent problems the provincial Conservative government of the day convened a Royal Commission to address.

Justice Patrick Hartt’s interim report in 1978 felt like a moment of recognition and vindication for Northern communities that had been out of sight, out of mind for too long. But even then, I remember one Royal Commission staffer speaking sceptically, colourfully and, unfortunately, off the record about how the recommendations would be received—and whether real action would follow. Now we can look back nearly five decades and realize how right he was.

Our Community Engagement Lead Lella Blumer was at the legislature Wednesday and brings the story up to the present day.

At the rally, we met a young couple from out of town who hadn't heard the Grassy Narrows story and asked us what our signs meant. After we explained it involved industrial dumping, and that governments of all political stripes had known about it for more than 50 years, they both nodded knowingly.

They told us they’d come to Canada from a(nother) part of the world where governments cover up industrial pollution and its impacts and ignore calls for action from citizens. Unlike the Canada that most urban dwellers know, it’s a place where confrontation happens openly and "people get shot in the street" for speaking up—whereas here, the damage is covered up.

They both looked unconvinced that calling on governments to take action would produce any results. But it struck a chord with them that it’s meaningful to exercise our rights and voices as citizens, show support for Grassy Narrows, and show them they’re not fighting for justice alone.

The Next Sacrifice Zones

The concept of a sacrifice zone is what draws a straight line from the deep betrayal of Grassy Narrows and Whitedog to the community impacts we can foresee from oil and gas infrastructure that has either gone out of production, or soon enough will.

The communities along the English-Wabigoon had their lives disrupted and their health deeply damaged before the companies responsible fled the scene. Now, as the oil and gas industry moves into its final decline, the next sacrifice zones are already taking shape—nowhere more obviously than in Alberta, where the cost of cleaning up a massive inventory of 300,000 unreclaimed wells has been estimated as high as $260 billion.

Provincial Energy Minister Brian Jean is hinting at the province’s thinking on how to deal with that gargantuan backlog. He mused last week that the province’s oil and gas industry might need help from taxpayer subsidies, lower municipal taxes, and lighter regulation to live up to its legal obligation to clean up its own mess.

We’re taking side bets that “lighter regulation” translates into cleanup standards and regulatory oversight that are even less rigorous than the province’s current practice.

All of this was just a few days before The Canadian Press reported that Alberta had helpfully returned $137 million in unused funds the federal government offered to get some of the well cleanups done.

"Why was that money not spent?" Duane Bratt, a political science professor at Calgary’s Mount Royal University, asked in a CBC interview. "The sector agrees it's important, the provincial government thinks it's important, the federal government has said it's important, resources were put in play, and they weren't used or they weren't fully used."

But even if every little bit helps, the federal dollars were really just a downpayment on clearing a huge, accumulated liability that traces back to the same casual carelessness that allowed the Dryden pulp mill to spew mercury into the English-Wabigoon river system.

The public cost estimate for the abandoned well cleanup, reported by The Canadian Press in 2021, was $40 to $70 billion, not including infrastructure like pipelines and pumping stations. In a private presentation in 2018, an executive with the Alberta Energy Regulator said the province actually faced a staggering $260 billion in estimated liabilities.

Based on AER data, Regan Boychuk of the Alberta Liabilities Disclosure Project warned in 2021 that 80% of the province’s oil and gas wells no longer held enough untapped resources to pay for their cleanup. The solution, he said, was for the public to take them over and use their remaining revenue to pay for remediation.

The provincial energy minister’s latest big idea suggests the Alberta government may not have got that memo.

A Slap on the Wrist

The AER is doing no better with the immediate health impacts of oil and gas development, administering a hearty slap on the wrist to Imperial Oil after the ExxonMobil subsidiary allowed water contaminated with arsenic, dissolved metals, and hydrocarbons to leak out of the tailings ponds at its Kearl oil sands facility over a period of years.

At the time, the AER maintained the fine was the maximum permitted under the provincial Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act. Administrative law experts later said the regulator chose to structure the fine to avoid an assessment that could have been 26 times higher.

“The CEO makes that in half a day, so it’s a slap on the wrist in regard to our community and our concerns,” Chief Allan Adam of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation told the Globe and Mail in late August. “They washed their hands clean and said, ‘Screw you, Fort Chip.’ If you ask the people of the community, they’ll tell you the same thing: The government doesn’t care about us.”

The First Nation warned community members to stay away from Lake Athabasca until water quality testing could be completed, but Fort Chipewyan Métis President Kendrick Cardinal said the health impacts in the area are old news.

“We’ve all known for the longest time that there’s something wrong with the water here,” he said in a Facebook video.

Communities Taking Charge

There’s at least one hopeful sign of communities gaining some control. In 2021, the British Columbia Supreme Court ruled that the cumulative impacts of natural resource development—including oil and gas, forestry, and hydropower development, all of which the province had actively promoted—prevented the Blueberry River First Nations from meaningfully exercising its treaty rights.

“Blueberry’s knowledge and its ability to successfully hunt, trap, fish, and gather depends on the health and relative stability of the environment,” Justice Emily Burke wrote in her ruling. “If forests are cut, or critical habitat destroyed, it is not as simple as finding another place to hunt. The Dane-zaa have located these places over generations.”

Eighteen months later, Blueberry River announced an agreement that would reopen its territory to oil and gas fracking but give it significantly more say in the way the work proceeds, after decades of being treated as collateral damage by policy-makers and industry.

That outcome doesn’t fully speak to the predicament facing Grassy Narrows, where the damage is done and any opportunity to take charge presumably begins with a cleanup effort that is six decades overdue. Progress of any kind has to start somewhere. But the Grassy Narrows rally last week was a reminder that the clock is ticking—and that decades, not weeks or months, can go by in a heartbeat while egregious damage goes unaddressed, with lives and health hanging in the balance.

Mitchell Beer traces his background in renewable energy and energy efficiency back to 1977, in climate change to 1997. Now he and the rest of the Energy Mix team scan 1,200 news headlines a week to pull together The Energy Mix, The Energy Mix Weekender, and our weekly feature digests, Cities & Communities and Heat & Power.

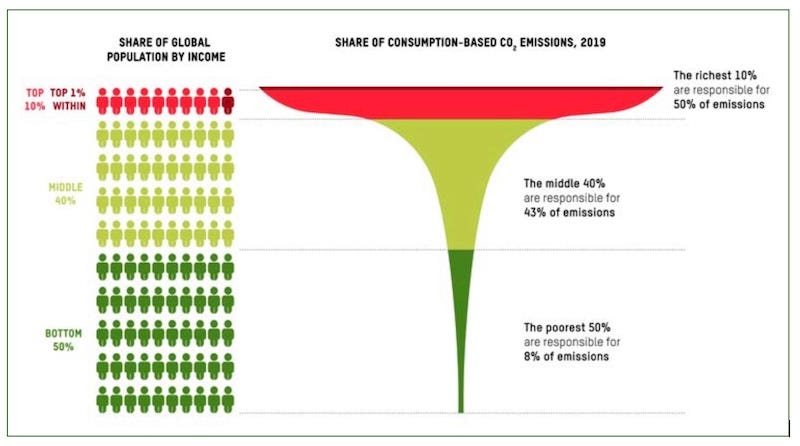

Chart of the Week

Glacier Melt, Greenland Tsunami Trigger 9 Days of Global Seismic Activity

Fossil Phaseout Pledge at Risk as UN Climate Finance Negotiations Bog Down

Renewables Could Cut EU Power Prices in Half by 2030, Report Predicts

Trump’s False Claim on Energy Transition Draws Rebuke from Germany

Heat Pump Surge Faces Hurdles with New Refrigerants, Lack of Technicians

‘Reality Gap’ Has Energy Transition Plans Crumbling Without Cash, Analysts Warn

‘Tragedy But Not An Anomaly’: EU Issues Stark Warning Amid ‘Climate Breakdown’

B.C. Receives 21 Bids for Clean Power Supply, Unveils Whole-Building Retrofits for MURBs

Passive House Training Program Tackles Skill Shortage in Low-Carbon Building

Irish company planning to produce jet fuel in Goldboro, NS, at former LNG site (The Canadian Press)

Will dreams of an offshore oil boom off Canada's East Coast go bust? (National Observer)

CDPQ, Fonds FTQ invest $575M in Énergir to spur renewable projects (SustainableBiz)

BP to sell its U.S. onshore wind energy business (Reuters)

UK Foreign Secretary Lammy says climate change more urgent threat than terrorism or Putin (The Independent)

Big Energy Issue in Pennsylvania Is Low Natural Gas Prices. Not Fracking. (New York Times)

Residents say Pennsylvania has failed communities after state studies linked fracking to child cancer (The Daily Climate)

Massive pipeline fire burning near Houston began after a vehicle struck a valve, officials say (The Associated Press)

Australian-based renewables and storage major fights unwelcome bid from ‘serial polluter’ (RenewEconomy)

Germany Set to Exceed Goal of 80 Pct Renewable Power by 2030 (Rigzone)

Silent Solar (The Crucial Years)

Scientists have captured Earth’s climate over the last 485 million years. Here’s the surprising place we stand now. (Washington Post)