A ‘Band-Aid on a Bullet Wound’ at COP29: What Will Bring Rich Countries Onboard for Climate Finance?

A “dumpster fire”. The “most horrendous climate negotiations in years”. A “band-aid on a bullet wound”. Where’s the political will to free up trillions of dollars for front-line climate solutions?

The COP29 climate summit finally tied up at about 3 AM this morning in Baku, Azerbaijan, with United Nations officials and some other COP veterans trying desperately to paste a happy face onto two weeks of largely futile, failed negotiations.

Any UN climate conference is bound to produce mixed results. That’s the reality of a process that demands consensus among 195 countries that often don’t much like or trust each other. But this year’s results were almost uniquely egregious, and the early reviews are scathing.

UN Climate Secretary Simon Stiell put the obligatory brave face on a $300-billion climate finance deal that doesn’t take effect until 2035 and falls vastly short of the $1.3 trillion developing countries were looking for. "This new finance goal is an insurance policy for humanity, amid worsening climate impacts hitting every country,” he said. “But like any insurance policy—it only works if premiums are paid in full, and on time. Promises must be kept, to protect billions of lives.”

He added that the agreement will still "keep the clean energy boom growing, helping all countries to share in its huge benefits: more jobs, stronger growth, cheaper and cleaner energy for all.”

Fortunately, not everyone onsite was forced to respond like a diplomat to a deeply offensive COP outcome.

“This has been the most horrendous climate negotiations in years due to the bad faith of developed countries,” declared Climate Action Network Executive Director Tasneem Essop, in a release headed “Betrayal in Baku”.

“COP29 was a dumpster fire. Except it’s not trash that’s burning—it’s our planet,” said Nikki Reisch, climate and energy director at the Center for International Environmental Law. “And developed countries are holding both the matches and the firehose.”

“A band-aid on a bullet wound,” concluded Climate Action Network Canada Executive Director Caroline Brouillette. “The fact that it’s a bigger band-aid than we’ve seen before is cold comfort when the world is also bleeding more heavily than ever.”

The team at Carbon Brief is already out with an exhaustive summary of what happened in Baku.

The Big Fail on Climate Finance

Throughout the two-week conference, we saw negotiations lag on key action items from the 2015 Paris Agreement, along with a concerted push by petrostate Saudi Arabia to suppress all mention of last year’s landmark commitment at COP28 to start phasing out fossil fuels.

By the time delegates arrived at the conference that was supposed to be the Finance COP, they’d all seen the analysis showing that $1.3 trillion per year was the price of entry to address the front-line impacts of climate change—and that rich countries could find the funds without trashing their own economies. Bearing in mind that the countries most severely affected by the climate emergency are also the ones that have done the least to pour climate-busting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Instead, negotiations hit a new low when developed countries offered a paltry $250 billion per year to meet the need. They eventually decided they could afford $300 billion, a year after the world spent $2.44 trillion on weapons of war.

“It’s ridiculous. With this number, they are spitting in our faces,” said Panama’s special representative for climate change, Juan Carlos Monterrey Gómez.

“We don’t take that seriously,” said Kenyan negotiator Ali Mohamed.

Photographer Kiara Worth, who has tirelessly and brilliantly chronicled the last several COPs on behalf of the UN climate secretariat, described the hours delegates spent waiting for a long-delayed closing plenary to finally get under way.

By mid-afternoon Saturday, “there was still no improvement on the new finance goal and you could cut the tension with a knife,” she wrote on LinkedIn. “Some delegates were huddling behind closed doors, others were making stressed calls to capitals, and civil society was demonstrating in the corridors, calling for the Global South to stand up, to hold the line, to fight back against injustice.”

By late afternoon, “it seemed like the negotiations might collapse,” Worth recounted. “Representatives from Least Developed Countries and small island states temporarily walked out, saying their demands were not heard and as the ‘moral compass of the world’ this was not acceptable. What will happen next? Who knows.”

In the end, developed countries threw a bit more money into the pot—with an important twist. “Under a compromise to get a deal over the line, rich nations eventually agreed to commit $50 billion more than what [the] draft agreement on Friday called for,” Bloomberg News reports. Crucially, “they had also made any agreement contingent on reaffirming last year’s COP28 outcome in Dubai that included a vow to transition away from fossil fuels.”

Disappointment at Every Turn

The low, low figure for climate finance was the most flagrant failure at this year’s COP. But there was more than enough disappointment to go around. Our friends at Climate & Capital Media compiled a list of greatest hits (by which we mean biggest misses) that includes:

• Failure to distinguish “grants and grant-equivalent funding” from loans that poor countries would have to pay back to lenders that originally got rich, in large part, on the proceeds of the fossil fuel era;

• “Insufficient and underwhelming” financing offers for climate change adaptation and loss and damage;

• A continuing standoff over who will host COP31 climate negotiations in 2026;

• Failure to connect the dots and coordinate efforts on the intersecting crises of climate change and biodiversity loss;

• What Carbon Market Watch called a “disappointing set of rules for a disappointingly open framework” for international carbon trading.

Climate & Capital was also one of a chorus of voices pointing to the malign incompetence of the Azerbaijani presidency itself, after President Mukhtar Babayev opened the conference by declaring oil and gas “a gift from God” and doing his best to drive countries away from the negotiating table.

“Attendees largely agreed that [Babayev] either had no idea what he was doing or did know but preferred the perception of chaos to any tangible outcomes,” Climate & Capital writes. “In addition, with the detention of a London School of Economic climate professor, whose research focuses on Azerbaijan’s oil and gas sectors, it has been a bad look all around.”

With Brazil set to host next year’s negotiations, the country’s Observatório do Clima went for dry understatement when it headlined its end-of-COP statement: “The COP30 in Brazil will require a high level of competence.”

Where’s the Political Space?

Behind the obligatory, celebratory rhetoric and forced optimism, the COP has always been a forum where countries come together to negotiate what they see as their best interests, not to work toward some shared vision of the common good. And look no farther than the routine, reflexive obstruction from petrostates like Saudi Arabia and Azerbaijan—or the 1,700-plus oil and gas lobbyists who once again flooded the zone at this year’s conference—to describe a process that is all about hardball politics, not good will.

It’s heartbreaking, infuriating, yet another missed opportunity on the road to eventually getting climate change under control.

But, seriously, are you surprised?

And the tougher question is: What will it take to build political space, then active public demand, for the world’s wealthiest countries to contribute their fair share to international climate finance? To show relatively supportive funders that they can do what it takes without triggering a grassroot revolt in their own countries, while letting more hostile governments know that this is one budget they don’t get to cut?

Some of the news coverage of this year’s COP at least clarifies a possible path—a long and winding path, at best—to building some of that support.

The reporting around the far smaller, $250- to $300-billion offer was a good measure that $1.3 trillion for climate finance was never an option—at least not entirely or primarily from government budgets, and certainly not at this year’s COP.

“Rich nations are grappling with a slew of fiscal and political constraints, including inflation, constrained budgets, and rising populism,” Bloomberg wrote. “The election of Donald Trump and his threat to pull the U.S. out of the landmark Paris climate agreement also hung over the COP29 summit early on.”

“Higher than thought,” one European negotiator told Politico after the $250-billion figure emerged. “Some in the group will have to go back to [their] capitals.”

In other words, a climate finance commitment that was pathetically low at the international level looked dangerously high to negotiators who knew their governments would eventually have to explain their decisions to voters back home.

A Long and Winding Path to Something Better

So here we are, yet again, at that tough, complicated inflection point between what we need to do and how we get it done.

Last week, for a story that wasn’t related to the COP, I talked to two of Canada’s climate philanthropy leaders, Environment Funders Canada Executive Director Devika Shah and Small Change Fund (SCF) President Burkhard Mausberg. Neither of them had any advance hint of what the other would say. But between them, they neatly summed up the community engagement challenge we face on climate and a winning approach to breaking the logjam.

“What we need is far more people power, grassroot cultural change, and political activism and engagement to provide the political currency that is required—what gives any politician, even Donald Trump, the licence to do good things for climate,” Shah said.

Building that support will mean arriving at a deeper understanding “of what climate change is going to mean for them and for all of us over the next five to 10 years, and most importantly, to a much better understanding of the big sources of power that are stealing power and resources from everyday people,” she added. “Because right now, that target is incorrectly pointed at the government,” not at polluting industries and the regulations that enable them.

How to make those connections is a whole other question. “We’re in a battle for the hearts and minds of Canadians,” Mausberg said. He cited past battles that environmental campaigners won—from the fight against acid rain in the 1980s, to the successful effort to turn local farmers from opponents to avid supporters of the Ontario Greenbelt—by reaching out, listening, and connecting beyond the environmental community’s core supporters.

Show Some Respect

“It comes down to respect,” said Mausberg, who founded the Greenbelt Foundation before eventually launching SCF years later. When the Greenbelt was first established, he recalled, farmers expressed their outrage by bringing their tractors to Toronto to encircle the legislature at Queen’s Park.

“So for the first two years, I got my boots dirty,” he said. “I went to farmers, to farm conventions, to farm supply shops, and asked, ‘what can I do to help you? What’s at the core of your concern?’” For bonus points, Mausberg often showed up in his beloved Toronto Maple Leafs sweater—and that common interest (or common sense of forever futility) gave the foundation founder and the front-line producers something they could agree on before they started in on the tougher issues.

Soon they found that those issues weren’t so tough, after all. “Invariably, they just wanted to be allowed to earn a decent living. Is that an unreasonable request? Of course not,” Mausberg recalled. “So we looked at how we could help them get their product to market and get the most amount of money for it.”

In the end, those common interests transcended the differences. “I’m an urban, downtown, Birkenstock-wearing, tree-hugging environmentalist,” he said. “But when we showed up, the first thing we showed was respect. We came to them. And that’s part of what we have to do on climate change.”

While there’s a universe of learning to glean from the Greenbelt Foundation’s success, there are so many other ways in which we’ve only just begun to break out of the climate “bubble”. When I had a chance to discuss this with a colleague in Toronto over the last week, she pointed to some recent successes in breaking down barriers to women entering clean energy jobs that are still predominantly held by men—but stressed that we still have a very long way to go.

Elsewhere, we’ve written about how to listen to the top concerns that isolated suburban moms bring to the climate conversation and connect from the ground up, rather than showing up with a fixed, outbound message and expecting to build trust. One of our team has recently started talking about “demessaging” our climate conversations, and I expect you’ll be hearing more about that in the weeks ahead.

The Greenbelt Foundation’s local connections occurred thousands of kilometres away from the negotiating rooms in Baku. And no amount of grassroot contact will solve a COP presidency so corrupt that it used this year’s conference to sign oil and gas deals on the sidelines of the negotiations.

But in one sense, everyone’s in the room when COP negotiations are under way—from the farmers in and around Ontario’s Greenbelt, to women trying to break into the clean energy industries, to fossil fuel communities that still expect mostly risk and not much reward from the transition off carbon. To everyone’s great detriment, the United States has just seen what happens when grassroot communities—when grassroot voters—become convinced that no one sees or hears them.

So yes, absolutely—it feels counter-intuitive, not to say brutal, to suggest that an urgent problem like international climate finance will only be solved at the speed of trust. But what if that turns out to be the quickest way or the only way to get the job done, and to make the solution stick?

If that’s right, we’d better make grassroot listening and bridge-building a far bigger priority than it’s ever been before.

Mitchell Beer traces his background in renewable energy and energy efficiency back to 1977, in climate change to 1997. Now he and the rest of the Energy Mix team scan 1,200 news headlines a week to pull together The Energy Mix, The Energy Mix Weekender, and our weekly feature digests, Cities & Communities and Heat & Power.

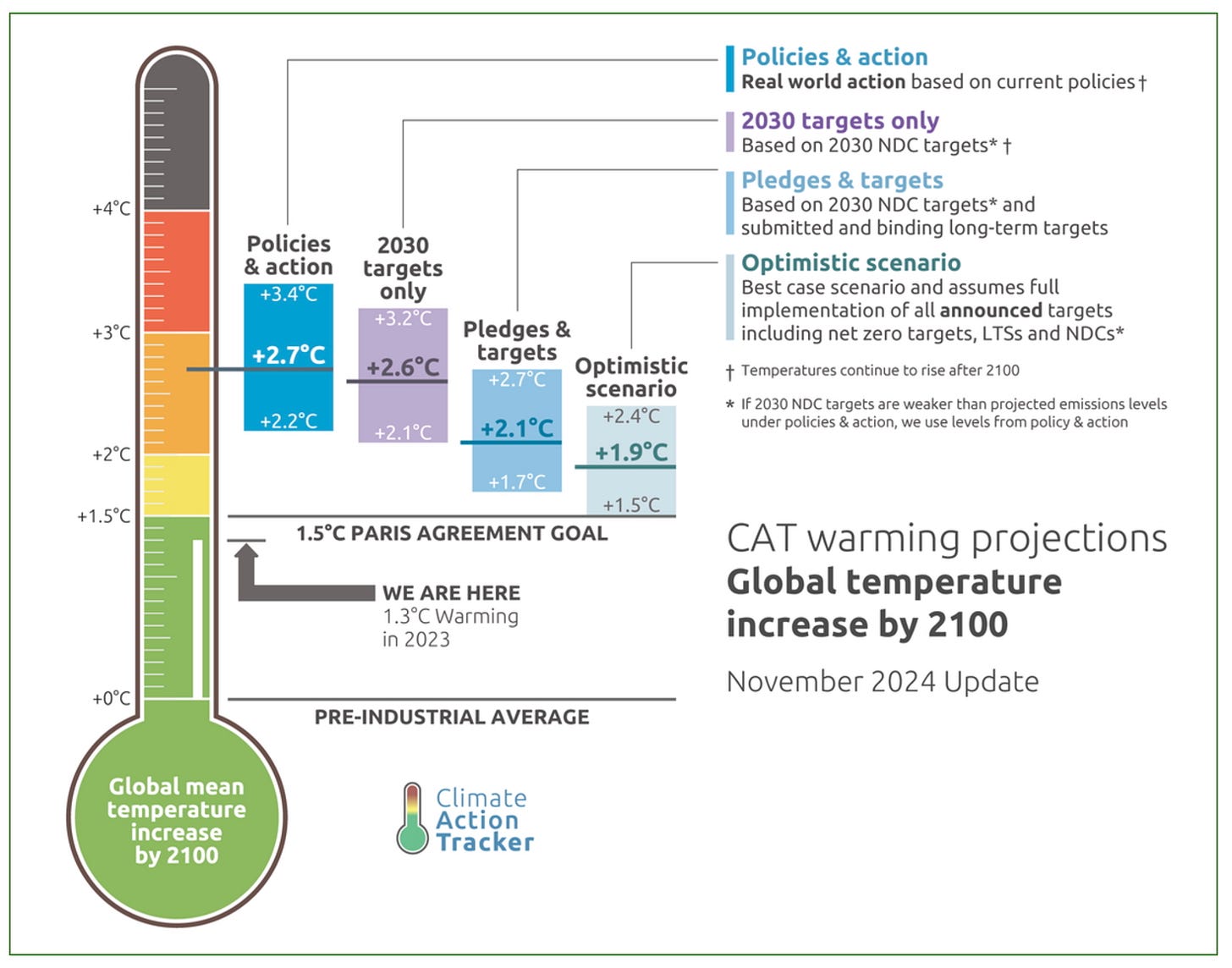

Chart of the Week

Quebec to Ban Gas in All Buildings by 2040

AIMCo Leadership Purged Over Spending Disputes, Critics Cite Political Motives

Winnipeg Ponders Gas Phaseout for All Buildings

Trump’s Policies Likely to Spare Canada, Set Back U.S. Energy Transition, Analysts Speculate

Use New Funding to Win ‘Hearts and Minds’, Experts Urge Climate Philanthropists

U.S. Battery Capacity Soars to Nuclear Scale, Creates ‘Golden Opportunity’ for Grids

Clean Energy Manufacturing Led Global Energy Job Growth in 2023

Power-Hungry Data Centres Can Become Grid Assets, Experts Say

Ottawa to Unveil High-Speed Rail Bid For Toronto–Quebec City Corridor

Alberta withholds results of public survey on renewable energy and agriculture (Calgary Herald)

Alberta joins pact with 12 states in bid to promote energy security after Trump victory (Globe and Mail)

Looming Trump tariffs drive rush on imports, push shipping costs higher (PV Magazine)

‘Net-zero’ banks raised $1 trillion for fossil fuel giants (Grist)

European LNG imports nearly a third more polluting than previously thought (Transport & Environment)

Natural gas supply is a bulk power reliability risk this winter: NERC (Utility Dive)

Over 420,000 children affected by record-breaking drought in the Amazon region (Unicef)

Bad Air Chokes the Life Out of a Vibrant Pakistani City (New York Times)

For green energy investors, grids could be the best bet (Investment News)

Decarbonizing manufacturing: Most processes are no longer ‘hard to abate’ (The Progress Playbook)

UAW launches campaign to unionize BlueOval SK battery workers in Hardin County (Kentucky Lantern)

At the Calgary Petroleum Club, a stage play reflects tension, polarization about Canada’s energy transition (Globe and Mail)

I would like to hear exactly what Canada's delegates supported or blocked at this year's COP. Regarding graph of the week: Climate communications have been hampered by focus on impacts in 2100. Most people do not care about what happens in 2100. Time to start reporting on shorter time frames like 2030 or 2040. Since climate warming is conveniently accelerating, it should be possible to still get dramatic graphics.