Nuclear Adopts ‘Emergency Framing’ Around Climate, But Still Can’t Deliver: M.V. Ramana

20 years ago, you would have been laughed out of the room for claiming that nuclear energy is clean technology. The urgency of the climate crisis has drawn some people to some strange conclusions.

A week off includes two weekends! So The Weekender is passing the mic to two of our favourite climate and energy writers. This week it’s our friend and former colleague Susan O’Donnell, adjunct research professor and lead investigator of the CEDAR project in the Environment & Society program at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, New Brunswick.

Despite nuclear energy’s notorious problems, the industry remains remarkably resilient, receiving solid support from governments around the world.

Most recently in Canada, a ministerial working group of federal cabinet members issued “a plan to modernize federal assessment and permitting processes to get clean growth projects built faster.” It includes aligning “federal, provincial, and industry resources to ensure nuclear energy remains a strategic asset to Canada now and into the future.”

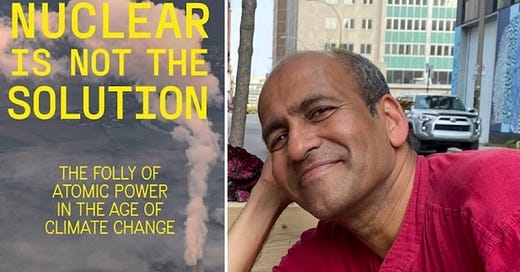

A prolific and well-known critic of the nuclear industry in Canada is physicist and professor M.V. Ramana, Simons Chair in Disarmament, Global and Human Security at the University of British Columbia. Ramana is back in Vancouver after spending the winter academic term at Princeton University in the U.S., where he previously worked as a researcher for many years.

I last spent time in person with Ramana in June in Montreal where we co-organized a conference panel on Challenging the Canadian Nuclear Establishment. We spoke by phone in July about his new book published this month, Nuclear is Not the Solution: The Folly of Atomic Power in the Age of Climate Change.

O’Donnell: Your last book was about nuclear power in India. Your new book is about nuclear energy and the climate crisis. Why did you want to write about that?

Ramana: About 20 or 30 years ago, if someone had talked about nuclear energy as an environmentally friendly, clean technology, they probably would have been laughed out of the room. But in the last decade or two, the nuclear industry seems to be succeeding in changing how people think of this technology, including some environmentalists who one would expect to be critical of the industry’s claims.

Much of that is the emergency framing, in which climate change is seen as the overwhelming problem, and we are asked to ignore every other consideration in addressing that.

Nuclear energy has several well-known problems. The fact that there could be catastrophic accidents has been proven time and again. There is no demonstrated solution to managing radioactive waste for the hundreds of thousands of years it will be hazardous. The link between nuclear weapons and nuclear energy. Climate change is framed as such an existential risk that we should overlook all these other problems.

This argument misses the question of whether nuclear energy is a feasible solution. This is the larger context in which I was trying to address the problem.

As well, these framings of nuclear energy as a solution to climate change miss the relationship between the nuclear industry, the fossil fuel industry, and other industries that prefer to maintain the status quo.

O’Donnell: I was at a meeting recently with climate activists who support more nuclear development, and someone said my opposition to nuclear energy is helping the fossil fuel industry. You just suggested the opposite.

Ramana: Their argument presumes fossil fuels can only be replaced by nuclear power and ignores the possibility that one might switch to renewables. It's a standard logical fallacy. Both the fossil fuel industry and the nuclear industry use this narrative. Both will claim that you cannot operate an electricity grid without so-called “baseload” sources of power, and fossil fuels and nuclear power are portrayed as the only options for producing that kind of power.

That form of thinking is outdated at this point. It was how people thought about managing an electricity grid back in the early part of the 20th century, ideas about trying to have power plants operating 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. So-called “baseload” plants [are meant to] meet the minimal electricity demand that is always present. And then for the much higher demands during certain periods of the day or the year, we will run other kinds of plants.

The growth of renewables goes against that form of thinking because renewables cannot be classified either as baseload or peak power. They generate when the wind is blowing or the sun is shining, and that forces us to rethink how we manage the grid.

We have come a long way from the idea that we cannot operate a grid using only renewables to understanding that the grid will be stable even with a very high proportion of renewables. If at all there's any question, it's about the last 10% or so. [And that’s why investment in battery storage has been surging—Ed.]

O’Donnell: Right now, among my colleagues, we're wondering if the small modular reactor “era” is coming to an end in Canada. Here in New Brunswick, it looks like the ARC reactor design is on its way out. Much of the hype in Canada now is about big reactors. We're seeing SNC Lavalin, rebranded as AtkinsRéalis, trying to sell their big, new 1000 MW CANDU design. We hear Bruce Power talking about building two new big reactors. The SMR companies are having difficulty getting the resources they need to reach the stage of applying for a licence to construct their reactor designs. Maybe in Canada we will skip over the SMR era, except for the one at Darlington, whenever that might be built, and just focus on refurbishments and big reactors.

Ramana: It depends on what you mean by “end of the SMR era.” Even the reactor at Darlington, the BWRX-300, is going to take another 10 to 15 years. During that period, at least, the SMR dream will be alive. The reactor will be much more expensive and take much longer, and so on, but one shouldn't underestimate the power of both the nuclear industry and its supporters within the government to keep pushing the idea that the next time around, it's going to be all fine. That has been their standard argument.

In the United States, for example, the AP 1000 reactors built at Vogtle were a complete failure by most measures, right? But now that the reactors have started functioning, you see people from the nuclear industry counting this as a great success. It's not that they're going to decide to build another set of reactors anytime soon, but you cannot rule out that possibility within, let's say, the next 10 or 15 years.

We see that in people like Jennifer Granholm, the U.S. Energy Secretary, talking about how much nuclear energy must expand over the next few decades, making an argument for more nuclear plants, whether they be small or big. The nuclear industry would want to argue that it's not a question of small versus large, it's going to be both. That's going to be their talking point, and they don't want to be asked to make a choice, because that infighting is going to weaken the other side, they understand that quite well.

O’Donnell: A chapter in your book deals with the high financial and temporal cost of nuclear energy. You show conclusively, and independent analysis backs you up, that nuclear power is more expensive and takes longer to build than renewable energy and storage.

You found a quote by President Macron of France, which is the most nuclearized state in the world, admitting that France needs to massively develop renewable energy to meet its immediate electricity needs because it takes 15 years to build a nuclear reactor. In the face of clear evidence, a lot of people question why France, and other countries including the UK and Canada, seem to be determined to build more nuclear reactors.

Ramana: The first reason is related to how these governments get advice on their energy strategies and policies. The advice tends to come from the very institutions invested in promoting nuclear energy. In the United States, it's the Department of Energy deciding on energy policy, and one of the Department of Energy’s priorities is to promote nuclear energy. It’s the same in Canada, it’s Natural Resources Canada giving the advice. There's an institutional bias towards nuclear energy present in the decisions made about energy policies.

The second reason is that the UK and France both have nuclear weapons. In both countries, the relationship between the nuclear energy sector and the capacity to make nuclear weapons, as well as the nuclear submarines used to deliver nuclear weapons, has been a talking point the nuclear industry uses to get government support. It's clear that policy-makers are thinking about this connection as a reason to support nuclear energy and make it flourish to the extent it can.

The last thing is that these countries look at the low-carbon nature of nuclear energy and see climate change as primarily a technical, maybe economic, issue. They think it can be fixed by changing what technologies we use to generate energy, with some taxes or cap-and-trade schemes to try and make sure the market values carbon in an adequate way.

There is no consideration of any deeper changes that we might need to make, towards society and the way we produce and consume materials and energy. That means nuclear energy or renewables are the only two options they can think about.

O’Donnell: Coming back to the financial aspects of nuclear power, I often hear that Bill Gates is famously supporting nuclear power, and you do mention him in your book. It’s a puzzle why billionaires, who you would assume are savvy with money, would support nuclear power if it's such a bad investment.

Ramana: They do invest some money, but only when they expect public funding to be a significant part of whatever project they are proposing. They can use public funding to then raise more money from private markets.

After the 2008 financial crisis, Silicon Valley billionaires had a dearth of investment opportunities for their financial holdings. They were trying to find things to invest in. Many of these investors have large portfolios, with every expectation that most of those investments will not materialize in major gains. But the hope is that if you put in 20 investments, and one of them makes a lot of money and becomes a Facebook-type success, that will more than compensate for all the others. And so, they usually look at these long shots [and say], even if there is a 1% probability, it's worth investing in.

People like Bill Gates and Sam Altman and others see technology as a kind of saviour for whatever they want to do. Climate change is a problem for them, because it looks like the effects of climate change might prevent business as usual from continuing, and business as usual is what has allowed them to become the very wealthy people they are. They want people to believe that climate change can be fixed using technological changes and that they themselves will be leading the investment in these technologies and solving climate change.

The challenge they see is that if people don't have this belief, they might start making more radical demands. I think I quote Sam Altman in one of my chapters, saying, “People then start thinking this crazy degrowth stuff,” which he calls “immoral” if I remember right. That kind of radical demand is something they don't want to see become more prominent. And so, technology is always portrayed as not just a saviour but also capable of solving climate change. They don’t want that central belief to be questioned. Nuclear energy is part of that portfolio of technologies they envision as solving the problem.

For these investors, the environmental and other risks associated with nuclear power are not challenges they think they’ll have to deal with. They are not going to live near a nuclear waste repository, or a uranium mine, or even a nuclear plant, so they're not particularly concerned about all these environmental impacts.

Nuclear is Not the Solution: The Folly of Atomic Power in the Age of Climate Change by M.V. Ramana was published by Verso Books on July 30 and is available as an e-book for C$11.20.

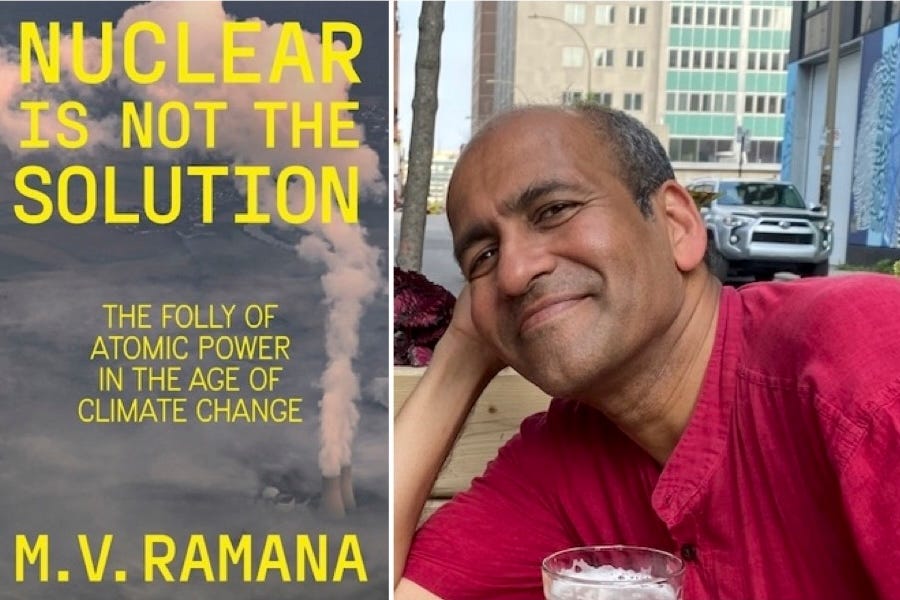

Infographic of the Week

Jasper Wildfire to Burn for Months as Mayor Voices ‘Shared Heartbreak’

#TBT: 13 Canadian Fossils Linked to Massive Losses in Western Wildfires

60-65°C: Extreme Heat, Humidity Hit Hardest for Poor, Disabled, Displaced, War-Torn

TransLink Warns of 50% Service Cut as Advocates Decry Gap in Operating Funds

Green Taxonomy Coming Soon with Tough Rules for ‘Transition’ Investments

Gas-to-Electricity Conversions in U.S. Hold Lessons for Canada

Markham, Ontario to Build World’s Biggest Wastewater Energy Transfer System

Vancouver Rolls Back Bylaw Restricting Gas Heat in New Buildings

Harris Brings History of Green New Deal Support, Fossil Fuel Lawsuits to U.S. Presidential Race

Toronto Councillor calls for charges after death of cyclist in Yorkville (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation)

UN attacks companies’ reliance on carbon credits to hit climate targets (Financial Times)

B.C. Tree Fruits co-operative shutting down after 88 years (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation)

Tree bark plays vital role in removing methane from atmosphere, study finds (The Guardian)

U.S. cities are raising climate ambition through subnational diplomacy (ICLEI/Smart Cities Dive)

The Ecoright: A conservative climate movement takes off (Climate & Capital Media)

The next Supreme Court setback for a Biden climate rule? (Politico)

Biden Administration Targets Domestic Emissions of Climate Super-Pollutant With Eye Toward U.S.-China Climate Agreement (Inside Climate News)

Ramaphosa finds pen and signs climate change bill into law (The Citizen/Johannesburg)

Looking From Space, Researchers Find Pollution Spiking Near E-Commerce Hubs (New York Times)

NATO’s 2023 military spending produced about 233 megatonnes of CO2 (The Guardian)

Green Steel Opportunities Fall Short of Investor Demand (Hellenic Shipping News)