The IPCC May Deliver Scary News This Week. But Climate Chaos is Not Inevitable.

This week’s UN climate report will likely be devastating. But we can still take the actions we need to get the climate emergency under control.

We’re still a couple of days from the release of the latest synthesis report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The findings are strictly confidential until they’re released, but it’s a good bet that the breaking headlines are already being roughed out—for better and for worse.

The good news about IPCC reports is that they get a lot of attention, generate a lot of coverage, and put solid, exhaustive science behind the reality that climate change is accelerating and at serious risk of spinning out of control.

The bad news is that the storyline almost always morphs into inevitability, in one of two ways: by wrongly feeding the fear that there’s nothing we can do about it, or forcing us to the conclusion that we’ll only get through this with exotic, new carbon removal technologies that force hideous choices about who benefits, and who pays the price.

Neither of those conclusions is necessarily right. They certainly aren’t inevitable.

Based on the half-dozen, multi-thousand-page reports that fed into this final synthesis, we can still avert the worst impacts of the climate crisis with a push for rapid, deep decarbonization that begins with a fast phaseout of fossil fuels. If we make the right choices now, we can do it without defaulting to pricey, unproven technologies that carry unpredictable risks, and may not even work—which means they may not even get us past the immediate crisis they’re meant to solve.

That frame will almost certainly be lost in the landslide of headlines you’re about to see. Any PR professional will tell you that sensational storylines sell, and many journalists and news outlets are conditioned to expect nothing less. But it’s still dangerous.

Because the truth behind the urgency of the IPCC report is that we are in an existential crisis, we do need to take action, but hitting those themes too hard or too exclusively is a guaranteed recipe for climate despair and fear. And the only way our best efforts are sure to fail is if we convince ourselves they already have.

So here are some things to bear in mind as the news deluge gets under way.

1.5° is Still Within Reach

Stephan Singer, senior climate science and energy specialist at Climate Action Network-International, says he’s been hearing the drumbeat for months.

“Isn’t it time to recognize that a 1.5°C limit on average global warming was a nice idea, but obviously unattainable given the cost of change and the political realities we face?”

“Even if we know that the difference between 1.5 and 2.0°C is measured in millions of lives lost, untold suffering, and massive environmental degradation, isn’t it time to accept that future, avoid these losses, and adapt as best we can?”

Those questions “are as predictable as the incremental, half-hearted result of this year’s United Nations climate conference, COP 27, in Egypt,” Singer wrote for The Energy Mix in mid-January. “And they’re as wrong-headed as a global fossil fuel industry determined to continue extracting a product that warms the atmosphere and devastates communities and ecosystems when used as directed.”

Singer argued that a 1.5°C limit on average global warming is achievable, affordable, and it’s ultimately about human justice—so even though it’s also intensely political, it’s time to get it done.

“When the fossil fuel lobby sends a bigger delegation to the 2021 UN climate conference than any country, then increases its numbers by another 100 in 2022, you get some idea of what’s holding up the drive for 1.5,” he said. While “limiting global warming to 1.5°C by the end of the century won’t be a paradise,” he adds, it will still deliver “a better future for all, and we can still get it done with the political will to curtail fossil fuels and shift trillions in global financial flows to practical, affordable solutions.”

It was the IPCC that entrenched the 2030 deadline to cut global greenhouse gas emissions by 45%. The agency’s science working group documented the “unimaginable, unforgiving world” we face if we miss the target. A relentless, 3,675-page “atlas of human suffering” from its impacts and adaptation group went into depth and detail on what’s at stake. And its mitigation working group called on governments to slam the brakes on carbon emissions to stay within a narrowing path to 1.5°C.

Expect all of that material and more to be folded into Monday’s report release.

But there are two essential rays of hope in the IPCC’s work: 1.5 is still possible with immediate, steep emission cuts; and structural change to reduce wasteful consumption can get 40 to 70% of the job done.

There are no guarantees that we’ll use the available time wisely to make the massive changes we need. While the recent leaps forward in renewable energy deployment are incredibly hopeful, the latest emissions data and the recent dash for gas, and even coal, are not.

But when researchers report that 56% of Canadian youth aged 16-25 are “feeling afraid, sad, anxious, and powerless” in the face of the climate emergency, and 78% say it’s affecting their mental health, it’s pretty clear that the bad and good news are seriously out of balance. That won’t likely change with the public narrative around this week’s IPCC report. But spreading realistic hope, as far and as fast as climate change itself spreads fear, is the only way to keep everyone in this fight—to help people cope with everyday life—over the long haul.

This Is How Good It Could Get

There have been so many moments big and small over the last intense, often horrid year when it’s been clear that not all is lost.

When the United States committed to US$379 billion in mostly clean climate investments, based on an unlikely alliance between the Biden White House and conservative Democrat Joe Manchin of West Virginia.

When European Union countries moved to speed up their own transition off carbon, after Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine drove home the message that they can never again be that dependent on anyone for energy.

When one 24-hour news cycle included separate, independent reports that renewable energy will deliver more than one-third of the world’s electricity by 2025 and as much as 90% of U.S. capacity by 2030, and accounted for 92% of India’s new generation last year.

When the federal natural resources minister declared that staffing up to fill all the available clean energy jobs will be a bigger challenge than finding good jobs for fossil fuel workers displaced by the transition off carbon.

When Indigenous Clean Energy reported nearly 200 renewables projects across Canada in operation or under development, each of them delivering at least a megawatt of power generating capacity. (This one actually dates back two years, but the good news at ICE hasn’t stopped pouring in.)

When Bloomberg reported that the decline of internal combustion vehicles began in 2017.

When long-duration battery start-up Form Energy announced 750 jobs at the new manufacturing plant it’s building in a poverty-stricken corner of Joe Manchin’s West Virginia, and the biggest solar investment in U.S. history brought 2,500 jobs to Georgia.

When start-ups like Toronto’s Li-Cycle began building businesses on the common sense reality that if you recycle more lithium from used batteries, you won’t need to separate as much from raw ore.

When six countries issued a declaration last week calling for a “just transition to a fossil fuel free Pacific”.

And that’s just a small, random sampling.

Then there was the webinar last year where the Covering Climate Now media collaborative amplified the best climate news you’ve never heard: that there’s still time for decisive action to stabilize global temperatures over a span of three or four years, rather than three or four decades, if only countries would move swiftly to bring greenhouse gas emissions to zero.

“The gist of this largely unknown science is that, contrary to long-held assumptions, large amounts of temperature rise are not necessarily locked into the Earth’s climate system,” CCNow co-founder and executive director Mark Hertsgaard said at the time. “As soon as emissions are cut to zero, temperature rise can stop in as little as three years. Three years, not the 30 to 40 years that almost all of us as journalists thought was the scientific consensus.”

The analysis still has to navigate scientific uncertainty on the details of key climate tipping points like ocean warming, the disintegration of major ice sheets, and the pace at which big, natural carbon stores like the Amazon are becoming net sources of emissions, Penn State climate scientist Michael Mann told the webinar. But the IPCC’s own models show that “if you stop emitting carbon, surface temperatures stabilize within a few years.”

You can predict with “very high confidence”, as the IPCC might say, that this line of thought will be lost in the conversation around this week’s science report. And that’s unfortunate. To deliver a complete picture of what’s going on, and to give people the heart and the hope to stay tuned for more, climate analysts and advocates need to learn to take the wins where we can, without easing off the pressure for more, better, and faster. We need it all. And we need all of it now.

Mitchell Beer traces his background in renewable energy and energy efficiency back to 1977, in climate change to 1997. Now he scans 1,200 news headlines a week to pull together The Energy Mix and The Energy Mix Weekender.

You can also bookmark our website for the latest news throughout the week.

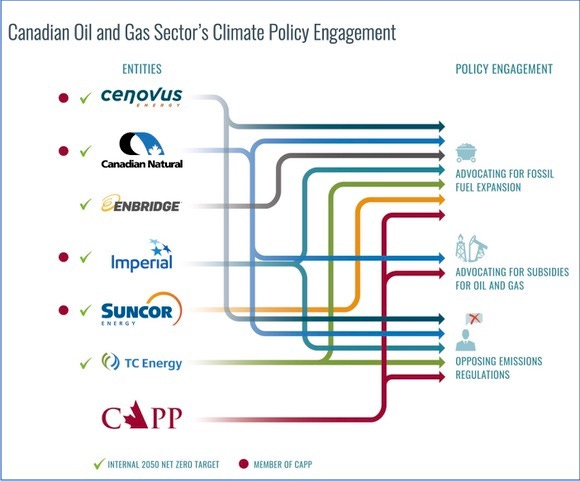

Infographic of the Week