Earth Day Founder Denis Hayes: ‘Let's Get Out There and Fight for This’

The first Earth Day in 1970 helped define modern environmentalism. After 53 years of making the case, Hayes says we still need an ‘aroused citizenry’ to finish the job.

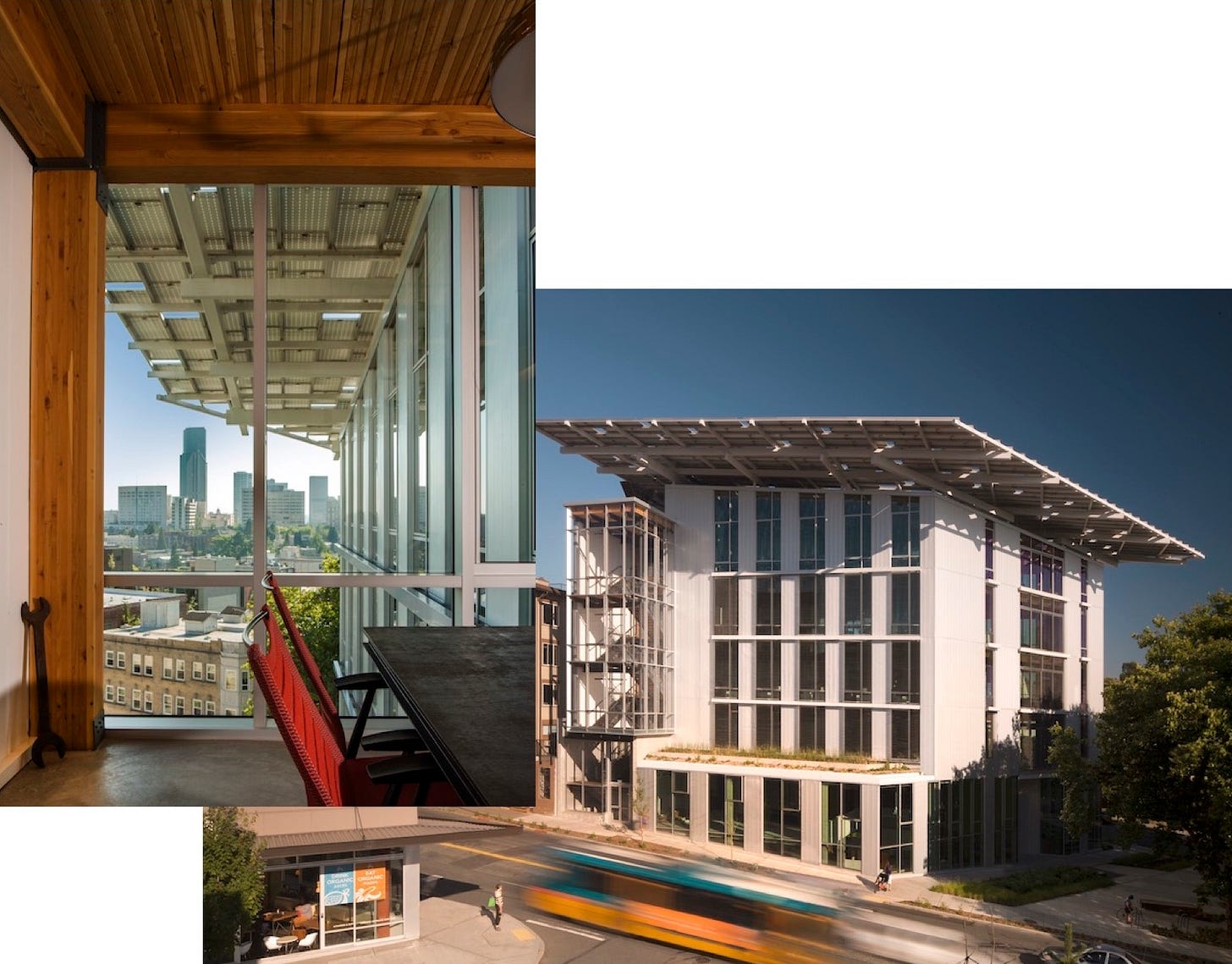

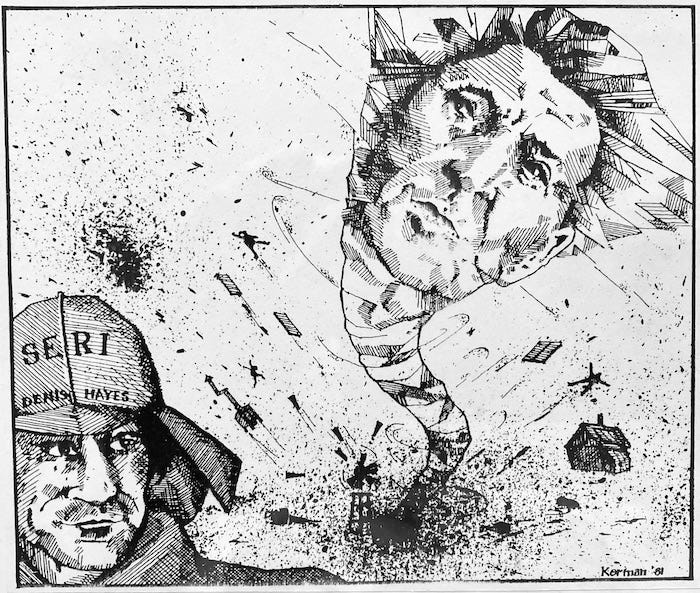

Denis Hayes is Chair and President of the Bullitt Foundation in Seattle and was coordinator of the first Earth Day in 1970, which drew an estimated 20 million participants. He founded the Earth Day Network, and later became the youngest-ever director of a U.S. national laboratory when President Jimmy Carter appointed him to lead the Solar Energy Research Institute in 1979. At the Bullitt Foundation, he's been promoting sustainable buildings and sustainable cities since 1992, operating out of the greenest commercial building in the world.

View the edited video here.

The Energy Mix: I'd like to start by taking you back to 1970, a time when environmental consciousness was beginning to dawn. What shifts have you seen in the technology, the politics, and in public momentum for the energy transition?

Denis Hayes: The changes are absolutely enormous. Remember that, back in 1970, there was no Internet, there was no social media, there was no ability to mobilize unless you had some way to reach people through conventional media who would then come back to you by sending you a postcard. Organizing today is dramatically easier than it was in those days.

But people didn't really think of energy. In 1970, there was oil and gas, there was nuclear, to a very, very limited extent, there was solar—I mean, very limited. No one really thought of efficiency as an energy source. And nobody clustered all of those things together.

And similarly, the environment did not really exist as a consuming public issue. There were people who were deeply concerned about oil spills, particularly after Santa Barbara, about water pollution, about air pollution, about freeways that were being cut through dynamic, prospering, inner city neighbourhoods. But none of them thought of themselves as having any connection with one another.

Earth Day managed to somehow assemble the massive outpouring of public concern that took all of these separate threads and literally hundreds more and wove them into the fabric of modern environmentalism. So that in 1969, the vast majority of Americans would not have had a working definition of what environmentalism is. By the end of 1970, a very strong majority, maybe 80%, referred to themselves as environmentalists.

The Mix: So from that starting point, why didn't this get done the first time?

Hayes: The reality of climate change was a very, very minority and unpopular view even 10 years after Earth Day, so no great shock that the Earth's climate wasn't an issue at all in 1970.

But we did, to some rather great extent, encourage the local groups to focus on whatever was important to them. If it was a freeway, then that's what the demonstration was about. If it was urban air pollution, if it was saving whales, it was that. And that's how we were able to take all these broad, diverse themes and get them integrated into something that was viewed as a coherent, integrated movement.

Start Where People Are At

The Mix: So you started where people were at—now, there's a concept!—and created a space where communities could talk about whatever most concerned them. Do you see that applying now to climate change and the energy transition?

Hayes: There's enough factual knowledge now circulating that I had hoped those local efforts would be informed by that. But we have the disturbing trend that has emerged in the last few years—often attributed, not without reason, to subversive activities by the oil and coal and electric utility industries—where local groups are saying, ‘Yeah, we want to address climate change, but don't put a wind farm there.’ Or ‘yeah, we want to stop climate change, but those solar collectors are really ugly. We don't want them in our neighbourhood.’

The Mix: Don't put it in my backyard.

Hayes: Yeah, exactly. In particular, this next year, if you look at the projects that are in the expansion budgets of utilities and independent power producers, upwards of 50% of all new energy capacity in the United States will be solar, another 30 or 35% of those projects are going to be wind, and the majority of those can’t hook up to the grid because of community opposition and other forces that are out there.

And then laying over all of this is, of course, is the very strong desire of the oil industry, the gas industry, the coal industry to be profitable growth engines into the future. For the most part, they will publicly say that can't go on indefinitely. But they surely want to keep going just as long as they can, funding grassroots groups that oppose renewable projects and doing other things that are simply mean. I don't know how these people can go to sleep at night, given what they do for a living.

Just Being Right Is Not Enough

The Mix: Through your work at the Bullitt Center, do you see where you've been able to help reshape our understanding of what's possible and achievable, particularly in retrofits of large buildings, but in energy efficiency and retrofits in general?

Hayes: The older I get, the more I recognize the complexity. And at the same time, I'm impatient with the recognition that we are getting deeper and deeper into the mire with each passing year. The longer we wait to get things moving aggressively forward, the harder it will be to get there in time.

When we set out to do the Bullitt building, one of the things I did was talk to a half-dozen of the greenest developers in the Pacific Northwest in my country. Asking them, you know, this is what we're setting out to do. Is it possible, and what steps do we need to put in place? What mistakes have you made? What should we learn?

And to a person, they said, you just can't do it. What you're trying to do defies physical laws. You cannot generate enough electricity with rooftop photovoltaics in the cloudiest major city in the contiguous 48 states to meet the plug loads of your building, much less operate the building itself.

We thought they were wrong. We built an ultra-efficient building. We searched and found tenants who were prepared to come in and get the most efficient computers, the most efficient printers, the most efficient task lighting, the most efficient everything, and to encourage the individual decision-making by the people there. And as a consequence, we have run a meaningful [energy] surplus, a 10% surplus every year. So it's not just energy neutral, it's energy positive. So, you know, that's kind of a big deal. We did it on time and on budget. And it's always been completely leased.

This was an economic success story, so we ought to be able to now really change things. But it turns out developers are incredibly risk averse. They've done something they've made money at for the last 25 years. So they're much more likely to do one thing differently, and then if that works, another thing, rather than, as we did, reconceptualize the building and throw everything in at once. And if they do reconceptualize the building, they can't get a bank that will finance it—no bank would finance the Bullitt Center, we had to put the foundation's endowment up as cross-collateral.

I had this view that if you could prove that you could do it, and it made economic sense, and it made physical sense, and your tenants loved it, and it was a huge asset, that there would be some sort of a scramble to follow….But 10 years later, we've had incredible difficulty working with the utility in Seattle to get them to apply this to anything. They've now done a residential building, they've done a medical building, as though there were some mysterious, different thing about different styles of buildings, rather than simply a base load that you're subtracting from. I think we now have 12 or 15 buildings in Seattle, after 10 years, that take advantage of this and drive down their energy consumption significantly.

So I realize I'm doing an exercise in pessimism here, but there needs to be something that causes a major discontinuity so that people really conceptualize things differently. This isn't a series of decisions by bureaucrats who mostly just don't want to shake things up too much, because that makes their jobs harder. It takes an aroused citizenry that simply demands, and we start moving.

Weaving a Fabric of Climate Urgency

The Mix: It's been almost two years now since we heard the International Energy Agency definitively say, no new coal, oil or gas developments are consistent with a 1.5° future. And we still see the fossil gas industry, in particular, clearly saying they’ll be hitting peak production in the late 2030s, which is utterly inconsistent with the science. What prospect do you see, what pathways to turn that around?

Hayes: I think this is true for the world, it's almost certainly true for America, that we do a lousy job of anticipating, but we can sometimes be a pretty good counterpuncher.

We have just in the last five, six years begun to see a big increase in reporting on hurricanes, tornadoes, droughts, floods, devastation in polar regions, the melting of glaciers, all of this now starting to carry a climate patina. I spoke of the value of Earth Day getting air pollution, water pollution, saving the whales, stopping freeways, constraining pesticides, all being viewed as the fabric of something that is large. We're now beginning to see that kind of integration taking place around climate, as well.

At some point, I think that becomes a tilting point where people say we just can't do this anymore. And even the folks who are now protesting against grid interconnections or protesting against rooftop solar, protesting against offshore wind, you're going to see [them saying] they still don't like that very much, but it's a whole lot better than a devastating hurricane every year. And at that point, I think it tilts over and the political system is still operating.

The Mix: What kind of mobilization do we need, and can you see it happening around you in the U.S. or elsewhere?

Hayes: Particularly in my country, and to some reasonable extent in your country, the polarization is really quite dramatic. And I've come more and more to think that my early perceptions of how stuff gets done were a little bit naïve. I thought it was all about making reasoned arguments that were almost unassailable, that if you do this, everyone will be better off. And now I'm increasingly, tragically, thinking that much of it has to do with personalities, with someone who emerges as trustworthy when people don't have time to understand the technicalities…

The Win That Could Have Been

[It might have been different if] we had started on this, as we intended to, in the Carter administration. Say you've been reelected in 1980, then we would have been able to do something like an Inflation Reduction Act and had the time to have this disperse throughout society. People make a whole series of decisions in their own best interests, and we get there.

Now, to the extent we do that, I'm afraid it’s necessarily going to be such a slow process that we'll get there, but it's going to be after the world has heated to 2°C, maybe 2.5°. That's not the end of the world, but it's certainly a permanently impoverished world. If you want to avoid it, I think we need something much more akin to [an industrial mobilization] across the entire American economy. I don't see a clear pathway to get there from here.

But in Darwinian terms, there is no survival value in pessimism. If you don't think you can pull it off, then you don't even try it.

The Mix: The question I really don't want to ask you, but maybe the question to end on is, do you see the potential for the climate emergency itself being that motivator, and becoming the motivator in time that we have a chance to turn things around?

Hayes: One of the sad things about the climate issue as it has evolved, and particularly as it's evolved in the minds of the very young, is that it is seen as a cliff or a series of cliffs looming out there. And if you fail to meet this point, then you have failed—temperature goes up 1.5°C, and it's all over. No, no, what you want to do is try to stop 1.6°, or 1.7°, or 1.8°, or 2.0°. That all or nothing thing made a fair amount of sense when the big existential threat was, and frankly in my mind still is, thermonuclear war. I mean, that happens, yeah, it's all over, so you do whatever it takes to stop that.

But with climate? There have already been some really bad things that have happened in a variety of places around the world. And there will be more because it's baked into the system. The question is, when will we be able to have an aroused citizenry as a consequence of that?

To have hope, you also have to have a vision of what it is that you're hoping for. Those [visions of sustainable systems] are beginning to evolve piecemeal, they're not getting a lot of visibility, and it's kind of boring news. But as those models begin to come alive, people can see that, ‘well, they're not asking us to give up anything, they're asking us to build a better world, and then one consequence of that is we're going to be limiting the amount of climate damage that's done’. The down side is that that's all rational, and there's this current of irrationality that a Trump-type figure evokes on the other side, and I think we have to have some similar kind of figure on our side.

The Mix: Is there anything you'd like to add?

Hayes: Through this whole interview, I've allowed myself to be slightly more bleak than I probably should. I'm not a guy who gets up in the morning and wails and tears clothing. As you look throughout nature, among the very most powerful instincts is a survival instinct. So if it becomes absolutely clear, and frankly, for me, it's clear we're not going to hit 1.5°, let's get 1.6. Let's get 1.8. Let's get just as much as we can, just as fast as we can. Let's get out there and fight for this.

This report has been edited.

Mitchell Beer traces his background in renewable energy and energy efficiency back to 1977, in climate change to 1997. Now he scans 1,200 news headlines a week to pull together The Energy Mix and The Energy Mix Weekender.

You can also bookmark our website for the latest news throughout the week.